My goal in this blog post is to try to get to the root of how JavaScript inheritance works in three cases: without explicitly doing it, using modern prototype-based inheritance, and using modern pseudo-class-based inheritance.

(This post is definitely not for beginners to JavaScript, but for someone who already knows it and wants to understand it a little deeper.)

Functions

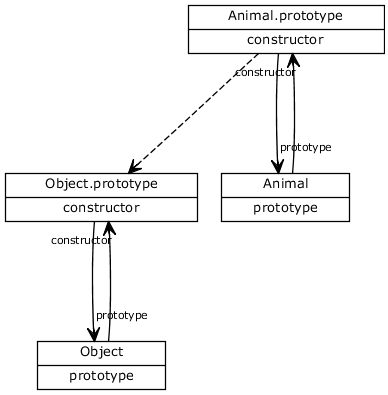

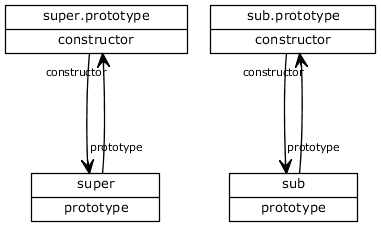

function Animal() { }On the surface, this code seems to create a function called Animal. But with JavaScript, the full truth is slightly more complicated. What actually happens when this code executes is that two objects are created. The first object, called Animal, is the constructor function itself. The second object, called Animal.prototype, has a property called Animal.prototype.constructor, which points to Animal. Animal has a property which points back to its prototype, Animal.prototype. This is illustrated in this diagram:

Although not shown in the diagram above, Animal.prototype actually inherits from the Object.prototype object. All objects in Javascript ultimately inherit from the Object.prototype object. A link from the object to the object it inherits from is stored in the internal __proto__ property (which is not publicly available in all browsers). The __proto__ property is illustrated in this diagram with a dashed line:

The "new" Operator

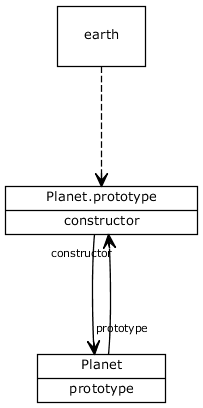

function Planet() { }

var earth = new Planet();JavaScript's built-in "new" operator is how JavaScript attempts to emulate class-based inheritance. The "new" operator creates a new object, in this case called "earth", calls the function "Planet" on it, then sets the __proto__ property of the new object to Planet.prototype.

This allows functions to act like classes in some ways, but creating a deep inheritance hierarchy is impossible using just the "new" operator. For example, how could you create a new class that inherits from the Planet "class"?

Using the "Object.create" Function to Implement Prototype-Based Inheritance

Because of the fact that most browsers do not let programmers directly access the __proto__ property, it is difficult to create objects in JavaScript that directly inherit from another object--the very definition of prototype-basd inheritance. To simplify this, Douglas Crockford discovered an improved way to create new objects in JavaScript. His function, illustrated below, creates an object which inherits from the object passed to the function, thus providing a simple method of implementing prototypal inheritance.

function createObject(parent) {

function TempClass() {}

TempClass.prototype = parent;

var child = new TempClass();

return child;

}

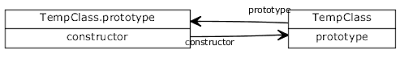

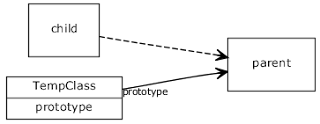

I will walk through what this function does one line at a time with diagrams.

1. function TempClass() {}

2. TempClass.prototype = parent

3. var child = new TempClass()

A version of this function is actually implemented on all the newer browsers (including Internet Explorer 9, Firefox 4, and Chrome 9) as "Object.create". But it is easy to implement it yourself if you need to support older browsers, using the formulation above or that described by Douglas Crockford in Prototypal Inheritance in JavaScript.

Using the Inherit Function to Emulate Class-Based Inheritance

Imagine that you wanted to use class-based inheritance in JavaScript. You might want to do something like this:

function Mammal() {

this.hasHair = true;

}

function Bear() {

Mammal.call(this); // Call parent constructor

this.roars = true;

}

inherit(Bear, Mammal);

var yogi = new Bear();

alert(yogi.hasHair); // This should display 'true'

Note the call to "Mammal.call" in the Bear constructor. This calls the parent constructor, similar to super() in Java or base() in C#. To implement the above, you can create some version of the "inherit" function:

function inherit(sub, super) {

var newSubPrototype = createObject(super.prototype);

newSubPrototype.constructor = sub;

sub.prototype = newSubPrototype;

}The inherit function takes two classes (functions) as parameters, and makes the first class inherit from the second one. In memory, here is how each line of the inherit function works...

1. Before the function is run, we have two classes, sub and super:

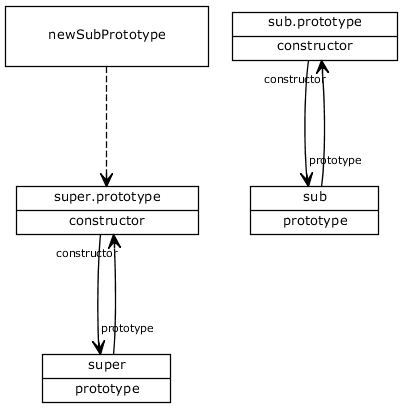

2. var newSubPrototype = createObject(super.prototype)

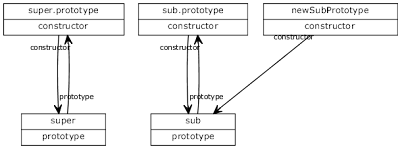

3. newSubPrototype.constructor = sub

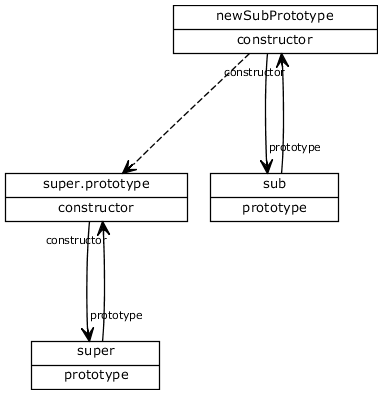

4. sub.prototype = newSubPrototype

Using one of these two methods can allow you to implement whichever inheritance scheme you like, which is one of the reasons why JavaScript can be so powerful if understood correctly.

Related Links

- Tim Caswell's Learning Javascript with Object Graphs, Part 2, and Part 3

- Dmitry A. Soshnikov's JavaScript. The core.

(A deep understanding of scope, inheritance, closures.) - Mozilla's JavaScript Reference

- Douglas Crockford's Prototypal Inheritance in JavaScript

(Updated 2011-04-23 - Additional clarifications based on comments.)

(Updated 2011-05-16 - Added missing call to super constructor in Bear constructor.)

(Updated 2011-05-16 - Added missing call to super constructor in Bear constructor.)

9 comments:

Hey Kevin,

IMHO your diagrams and code examples are utterly confusing for js newcomers! :) Even expanded it comes down to this:

function Mammal() {}

function Bear() {}

// createObject

function TempClass() {}

TempClass.prototype = Mammal.prototype;

// inherit

var newSubPrototype = new TempClass();

newSubPrototype.constructor = Bear;

Bear.prototype = newSubPrototype;

Notice how we create an intermediate class between Mammal and Bear. This is to avoid executing the super constructor function during the inheritance defining process. Useful though unnecessary.

Here is a better example:

function Mammal() {}

function Bear() {}

Bear.prototype = new Mammal();

Bear.prototype.constructor = Bear;

Cheers

Thanks for your comment, Δημητριος. Agreed, they would be confusing for JS newcomers. This post is probably best for someone in the middle, who knows JavaScript, but not deeply.

In practical cases, the best way to teach someone how to use JS inheritance would be to have them just learn one library's inheritance mechanism (Google Closure, Dojo, etc.) or just use ECMAScript 5's Object.create.

--Kevin

Hi Kevin,

You claimed that the behaviour of new is strange without adequately explaining it. Some more explanation might help.

Regards,

Dinesh

Hi Dinesh,

Thanks for your comment. Based on what you and Δημητριος pointed out, I did a little revising to clarify the points I was trying to make.

Hi Kevin,

we are trying your code and the inherits() function is not working.

As you can see here: http://jsfiddle.net/3pRuY/

There's also an implementation based on the comments of Δημητριος that is working perfectly:

function inherits(sub, super) {

sub.prototype = new super();

sub.prototype.constructor = sub;

}

BTW good explanations!

Cheers.

Hi Vilson,

Thanks for catching the mistake. I did indeed leave something important out of that code example: the call to the base class! I have fixed it in the code now. You can see it working now as well on this Fiddle example: http://jsfiddle.net/CXtdp/

Comparing the approach I used to the approach that Δημητριος pointed out, there are important differences. Δημητριος's inherits method is certainly simpler, but if the base constructor took arguments, it would not work. The one that I show in the blog post allows the child constructor to call the parent constructor with whatever arguments you want.

Both are totally legitimate options, you just need to understand the drawbacks of them.

Regards,

Kevin

Hi all,

Overall from my experience, the concept of an actual private variable in JavaScript is very rarely used, except for singleton classes (classes that can only have one instance). Otherwise, most programmers usually just denote a private variable in some way (usually with a prefixed underscore), even though they can really be accessed just as public variables.

Regards,

Jackie Bolinsky

I was writing JavaScript Confusing Bits going through whatever I found confusing while my JavaScript studies, when I found your post. It made me stop here for a while. Inheritance is one of those things definitely but I decided to skip it as it deserves own article I suppose. There is not a lot of good quality content out there explaining how the whole inheritance work. Thanks a lot for the article. Good job! Your blog goes CTRL + D :) Cheers

Nice post. I've been searching for a simple inheritance scheme that allows for two things:

1) Constructor method not called when the inheritance chain is set up. Contrary to what the commenter above says, this is not a trivial difference --- calling the constructor to create the prototype object means that the super object's data members (set by "this.property = foo) are shared by all subclass instances, rather than created for each instance. Also, what if the superclass constructor is supposed to do things, like call AJAX methods or do other complicated initialization? It's ridiculous to have that happen when all you're trying to do is set up an inheritance chain for the purpose of method inheritance only. This scheme avoids these difficulties. Other, more involved subclassing libraries also do this, but your post is the absolute smallest I've seen in terms of code size.

2) As you mentioned, the subclass constructor can call the superclass constructor with arguments. Another big advantage of your scheme.

I don't quite see the point of having a "createObject()" function, however. I just created a single inherit() method that does everything in one go:

function inherit(subclass, superclass) {

function TempClass() {}

TempClass.prototype = superclass.prototype;

var newSubPrototype = new TempClass();

newSubPrototype.constructor = subclass;

subclass.prototype = newSubPrototype;

}

Post a Comment